Freytag’s Pyramid

This is part of Write City Blog’s ongoing Writing 606 series, which will examine and compare several story structure methods over the coming months.

I remember my first creative writing teacher drawing a pyramid on the board, labeling its parts, and telling the class it was “the way” to structure a story. Freytag’s Pyramid is a simple tool created to analyze Shakespearean dramas and Greek, and it’s commonly used to teach new writers the fundamental parts of a story. However, its simplicity and original design limit its usefulness for complex stories and analyzing non-Western styles and certain genres. On the other hand, it’s a great place to start Write City Blog’s new Writing 606 series, which will examine and compare several writing frameworks over the coming months.

What is the Pyramid?

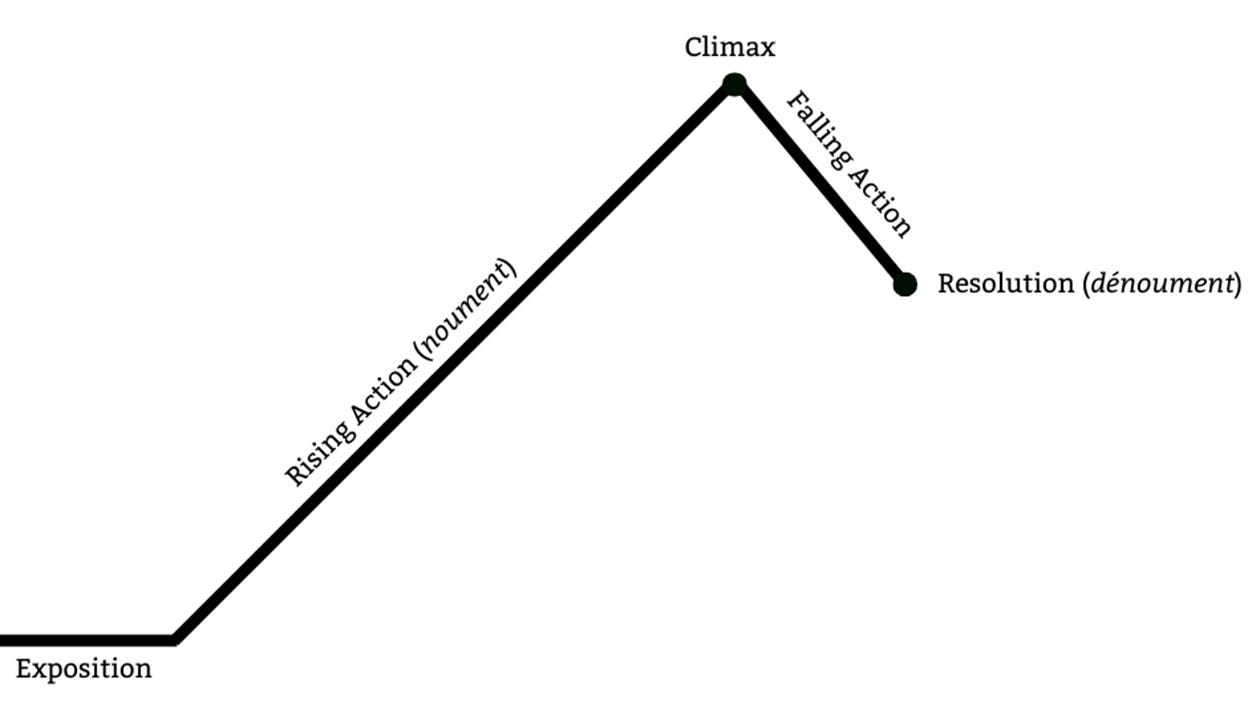

There are five elements in Freytag’s pyramid. It begins with exposition, the backstory that establishes our characters’ normal world and makes the events that follow significant. This is followed by the noument (knotting up), also known as the rising action. The rising action is a series of setbacks and complications that increase tension and lead to the climax, a crisis for the main character. The falling action is a relatively brief bit of narrative that leads to the dénouement (unknotting), more commonly known as the resolution.

Making the Pyramid Yours

With a few tweaks, you can modify the pyramid structure to fit most writing genres.

Fantasy writers may choose to extend the exposition for the world-building and historical detail that fans of the genre love.

Romance authors often stretch out the rising action to establish complex relationships between characters and maximize tension throughout most of the story.

Murder/mystery writers can also bump the climax as close to the end of the story as possible to introduce exciting twists before the big reveal.

Turn the “whodunit” into a “how will they solve it,” like in the TV series Columbo, by inverting the pyramid and putting the reveal at the beginning of the story.

This is ok for novels, but short stories may not have a falling action or resolution. In some cases, the climax and the resolution are one and the same. This doesn’t mean you can’t use Freytag’s pyramid for short stories, but just know that the end of the graph might look pretty scrunched up for these stories.

Tradeoffs

The simplicity of Freytag’s model makes it a decent analytical tool, but it also limits its usefulness as a guide for more advanced writers.

Advantages

With the exposition up front, you have plenty of opportunities for foreshadowing.

The style is flexible and adjusts to fit most genres.

It is compatible with other story structures, such as the Hero’s Journey.

With fewer parts than other frameworks, it's a great way to get a high-level view of your story.

Disadvantages

Not all writers start with exposition. It’s common to place the exposition after the inciting incident, like in the in medias res style, which starts in the middle of the action and explains the backstory once the reader has had a chance to get attached to the main character. As a teacher of mine used to advise, “No exposition before Chapter 4.”

There is a Western bias to this structure, so it is not as useful for analyzing or writing in the kishōtenketsu style, for instance, which is a narrative structure from East Asia.

Designed as an analytical tool, the pyramid looks at stories told in a purely linear way, which may not be how the story is told. However, this is only a drawback if writers assume that they must tell the story in this order and cannot shift elements around for heightened effect. Getting a linear view of your story’s timeline is important, but a good plot doesn’t always flow this way.

Despite its limitations, Freytag’s pyramid is an excellent place to start our new Writing 606 series. Due to its simplicity and ubiquity in writing classes, it serves as a good base reference for other writing structures we will look at.

Next month, we will take a look at the Hero’s Journey in more detail. Was Joseph Conrad right that all stories come back to the same basic pattern? Or did he oversimplify stories from around the world to fit into his model?

Sources:

Writing Fiction, by Janet Burroway

On Writing in General and the Short Story in Particular, by Rust Hills

Plottr (Freytag’s Pyramid Template)

https://www.thenovelry.com/blog/rising-action

Good stuff

Great point about not necessarily starting with exposition. It made me think of all of the detailed info-dumping about the Hobbits' world in Tolkien, within the prologue, vs more modern fantasy titles that often start in medias res or have a more cinematic, pace-oriented opening.

Thanks for citing Plottr's template, too! - Jordan at Plottr